Let me know if this reads well.

Well, I’ll Be Damned

Well, I’ll Be Damned

By Dan Kelly

I knew I’d grow up to be a writer. It never occurred to me I’d be a church reviewer.

Heck, I didn’t even come up with the concept. Brett McNeil, former Chicago Journal editor did. A decade ago, as Brett mentions in his foreword, Tom Frank of the Baffler introduced us at a party. Brett was looking for writers; I was looking for ink, money, and ego satisfaction. As two ex-southwest suburban Chicago kids we got along famously, and he asked me to send him a few clippings and pitches to get a feel for my work.

Writing for the Journal had one stipulation. Journalistically land-locked, it covered the beat bordered by Lake Michigan, Cermak Road, Lake Street, and Western Avenue. As long as I stayed within those boundaries, I could write about anything I liked. I confessed to Brett I was familiar with the area only in macrocosm, so assignments were appreciated. He said he’d think about it.

A few days later, Brett called and asked, “Dan, how’d you like to be a church reviewer?”

I laughed, then cursed myself for not thinking of it first.

I told him it sounded great, but what exactly did he have in mind? Visiting various houses of worship in the area, primarily, and approaching the experience as if I were critiquing a play, making notes about atmosphere, accommodations, and entertainment value. Mainly, I should answer the question “What’s going on in there?”

Therein lay the idea’s brilliance.

Houses of worship are surrounded by invisible, consensual force fields, most humans having an aversion to entering holy places not their own. Funny that, because—with a few exceptions, and with only minor etiquette requests—the doors are usually open to all comers. How else, gentle reader, do you think religions expand and thrive?

Whence comes this reluctance to enter religious buildings, much less to attend other religious services? Bigotry, mildly warm to boiling, is one reason. If you were raised in a particular faith, part of your inculcation likely involved a variation on the theme of “WE are right, THEY are wrong, and what’s more, THEY are DAMNED.” Even in the 21st Century some people still believe the earth will yawn wide and gobble them up if they nibble a cupcake from another faith’s bake sale. More likely, it’s based on the fact that religious services, lacking in visible sex and violence, just aren’t a big draw. If you skip mass on Sunday, it’s doubtful you’ll visit Friday afternoon Salat at the mosque, or Saturday Shacharit at the synagogue, for funsies.

Largely, I think, it’s based in fear. Fear of evangelization and harassment by goony-eyed true believers. Fear of accidentally offending the regulars by desecrating a chalice or toppling the tabernacle—risking public humiliation or a sacrificial dagger in the heart. Fear of, in short, the unknown. Cultural terra incognita exists in the heart of the Chicago Loop.

“What’s going on in there?” I visited several services to find out.

*****

Church reviewer wasn’t an entirely precise title, but Brett and I agreed a church reviewer I’d be, whether I was visiting a cathedral, temple, synagogue, mosque, or Chicago’s Stonehenge equivalent (Daley Plaza?). House of worship reviewer just doesn’t sing, yes? If I was approached by one of the religious elect during a story, I never used the term church reviewer. I’d say I was the Journal’s religious writer, covering the neighborhood deity beat. I remained visible but unobtrusive. I’d sit in the back, accept all literature passed my way, surreptitiously took notes, dropped in a couple of bucks as an admission fee at collection time, and generally avoided making an ass of myself. A devout introvert, I would have left it at that, but Brett (a damned extrovert) pressed me to speak with the parishioners and resident clerics for the human touch. I received a few suspicious looks when I identified myself (they always seemed a tad disappointed I wasn’t a potential acolyte), but largely I was welcomed. The services weren’t all barn-burners, but I was rarely bored. Burned out on Catholic Mass Repetition Syndrome, even the driest service was interesting simply because I had no idea what the hell was happening. As theater, I liked it better than real theater.

Brett had one other rule: “Don’t leave them crying at their altars.” I understood that to mean, “Don’t be a dick.”

My personal religious beliefs are complicated. Raised Roman Catholic, I currently attend an Episcopal church (the one my son was baptized in) and I participate in several of its services and events. I even gave tours of the building—a gentlemanly 1888 Gothic revival church—during a house walk. Yet, as much as I like the place and people, I’m not interested in converting just yet. In fact, I don’t think of myself as religious in the typical sense. I like to think I’m a philosophical Christian—the Beatitudes and the less judgmental parts of Paul’s letters are good guides to a kind, considerate life—with Deist leanings and a little Marcus Aurelius pragmatism thrown in. Nonetheless, I can see an excellent case for agnosticism. Maybe. I can’t say for sure.

Unlike the fundamentalist smart-asses on either side, however, I believe that—save that they harm none and admit the world works scientifically—there’s little point in denigrating or damning anyone for their religious beliefs. So, I guess I have a little bit of Buddhist and Wiccan in me as well.

While I knew I’d find a few laughs amongst the elect, I mostly wanted to play it straight, avoiding excessive snickering, ironical winking, self-promotion, or similar tactics from the hipster journalist playbook. Entering a house of worship and mocking the squares is too easy; so is entering a place in a state of pig ignorance, and I always read up on a religion before attending a service. No, I never wanted to convert, but I always wanted to learn. I remember a certain pop cultural critic saying (in so many words), “You can disagree with a religion, but you can’t just dismiss several thousand years of history.” Every religion has had its periods of evil insanity and pernicious groupthink, true, but if it inspires, for instance, the Book of Kells, Paradise Lost, and Tallis’ Spem in Alium, it can’t be all bad.

Don’t be a dick? Mission accomplished. Though one angry Christian Scientist letter writer disagreed. He also found me pretentious and thought I used too many $10 words. My goodness. Well, what can one say to that but, de gustibus non disputandum est?

*****

I have my regrets, but only about what I didn’t or couldn’t do with the series. The Journal’s borders and demographics heavily favored Christian churches. Finding a Loop synagogue or a mosque was a cinch; locating a Hindu or Mormon temple, a Sikh gurdwara, or an above-ground satanic coven somewhere on LaSalle, Wabash, or Ashland? Not so easy. St. John Cantius was the single cheat Brett allowed me, but only because it was within driving distance.

The most disheartening service I attended took place down in Chinatown—the pagoda-like exterior belying the vanilla Christianity taking place inside. When the preacher fired up an overhead projector and starting his PowerPoint presentation on soul-winning, I walked out for the first and only time in my church-reviewing career. Curse the new American prosperity religions and their aversion to tradition and mystery! A Catholic kids’ pretend mass, conducted on a card table and using Nilla communion wafers, has more soul.

Then there were the folks who said, “Thanks, but no thanks.” The I AM Temple people were pleasant hosts, walking me through the mysterious innards of their astonishing 12-story building on Washington Street and telling me, very politely, they didn’t offer interviews or let non-devotees attend services because they feared misrepresentation. They were probably right. What I saw and the little bit of the service I heard piped into the waiting room pushed the envelope of sanity screaming off the ledge. I would have had a field day with the Munchkin-voiced lady screeching about the all-enveloping purple ray of righteousness—or whatever it was. They tried to sign me up as an I AM’er too, telling me I’d obviously been sent to them by (dramatic pause) SOMETHING. If that were the case I’d be the only Methodist Christian Catholic Muslim Scientist Baptist Et Cetera Jew in Chicago by now.

*****

“What’s going on in there?”

Way back in Catholic grade school, one particularly old and odd nun warned us about the perils of attending other religious services (especially, for some reason, Baptists’—her tone suggesting they were satanic cannibals cabals). Such foolhardiness would only serve to confuse us, putting strange ideas into our heads and causing us to drift away not only from Catholicism but also religion, God, and Life Eternal. Funnily enough, being a church reviewer had the opposite effect. I started out a lapsed Catholic and I ended up, well, a wavering agnostic. Still, I learned a few things about what motivated my fellow primates by going where I wasn’t “supposed” to go, and I discovered there were more similarities than differences between us. Maybe that’s what worried Sister P.

I’m risking ending on a goopy ecumenical note, so I should add a few less Pollyannan thoughts. I’ve got to admit, a few times, at the services, I heard things I didn’t agree with—particularly in the “WE are right, THEY are wrong” category—or which reminded me of something atheist par excellence H. L. Mencken wrote:

“There is, in fact, nothing about religious opinions that entitles them to any more respect than other opinions get. On the contrary, they tend to be noticeably silly.”

Regardless, the more services I attended, the more consistency I saw in human ideals. Pushing past the hellfire rhetoric; the “My Ancient and Opaque Holy Book Is Better Than Yours” battles; and the occasional Neanderthal to medieval attitudes about this or that chunk of the population, at base every service was about community, sharing, and interacting with other humans in the quiet confines of a special building. I may not have agreed with everything I heard (and fortunately, I never heard anything particularly loathsome or brain-dead), but I never saw anyone get hurt or hurt anyone else by sitting in a house of worship, alone with his or her thoughts and god. Frankly, it was always a nice break from the rest of the week, if not the world.

Dan Kelly, November 2010

www.mrdankelly.com

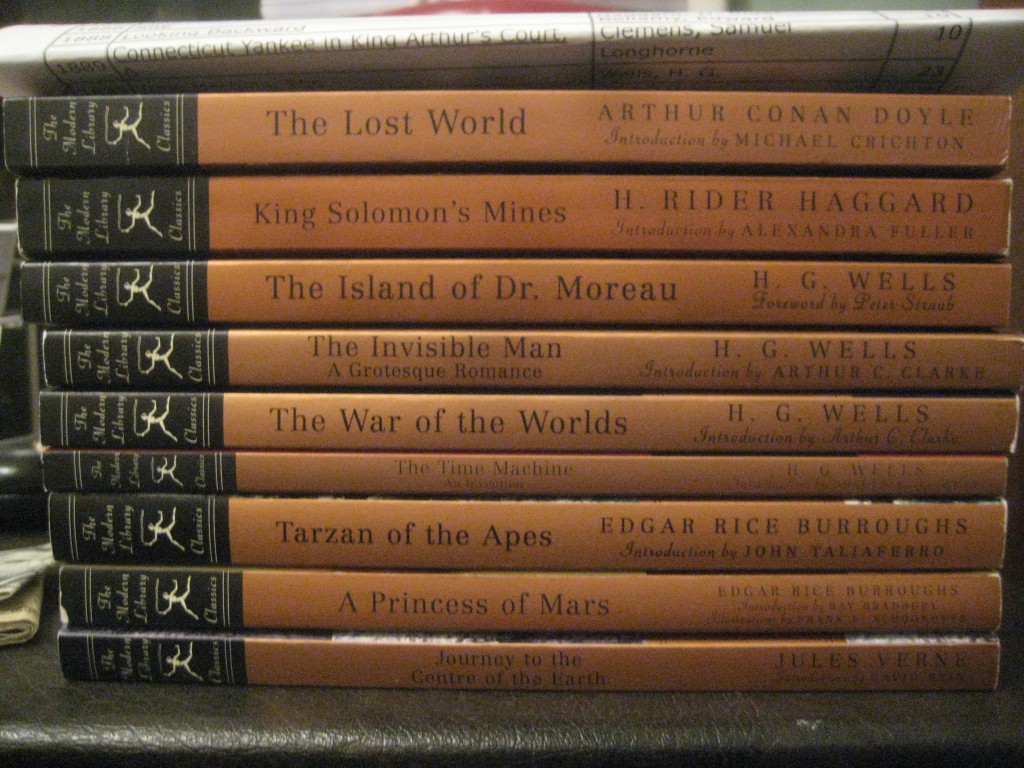

Sturgeon’s Law states that 90 percent of everything is crap. Kelly’s Corollary adds that 99 percent of that remaining 10 percent is simply good. In art, good is largely preferable to bad—save in the case of something being “so bad it’s good”… but that’s another matter. Good is enjoyable, intelligent, savory, and consistently acceptable, and that’s just fine. Where we run into a problem is when good is inappropriately celebrated as extraordinary.

Sturgeon’s Law states that 90 percent of everything is crap. Kelly’s Corollary adds that 99 percent of that remaining 10 percent is simply good. In art, good is largely preferable to bad—save in the case of something being “so bad it’s good”… but that’s another matter. Good is enjoyable, intelligent, savory, and consistently acceptable, and that’s just fine. Where we run into a problem is when good is inappropriately celebrated as extraordinary.